I have written before on how certain ideas or even quotations can encapsulate a whole set of practices. In my mind, democratising culture and cultural democracy are two of these essential concepts that offer a compelling theoretical rationale for gallery education and audience-focused museum practices more broadly.

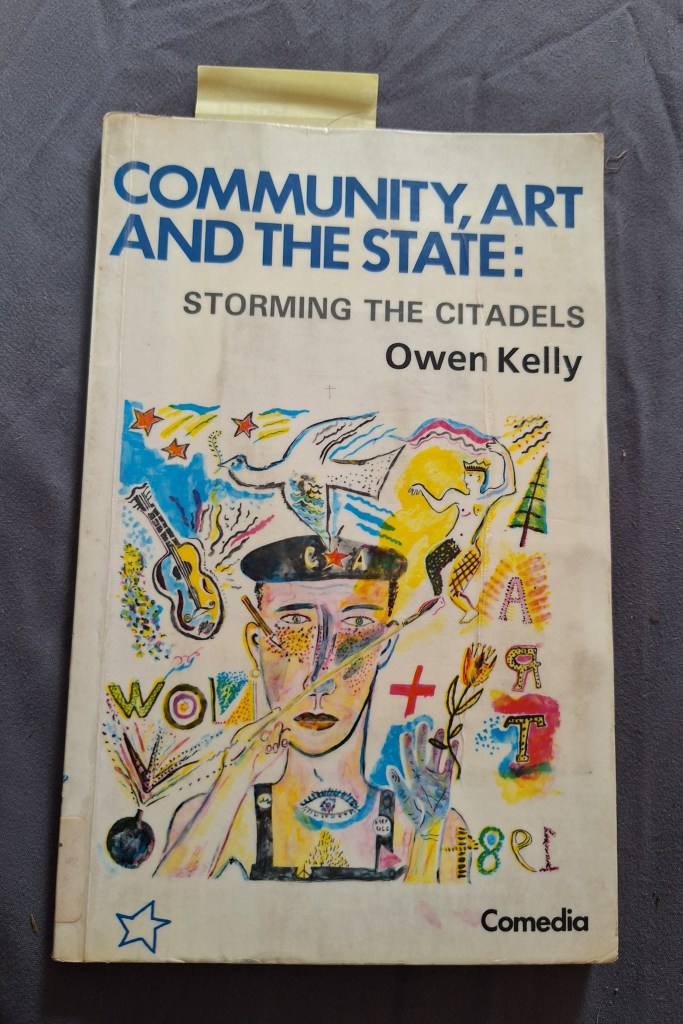

I first came across the concepts of democratising culture and cultural democracy in the late 1990s in Owen Kelly’s excellent polemical text on the development of community art in the UK that was first published in 1984. In chapter 14 of the book Kelly takes issue with the argument that what can be understood as ‘high culture’ in the form of ballet, theatre, painting, sculpture, and opera needs to be democratised through education programmes and ‘intelligent popularisation’ so that those beyond the middle classes might be persuaded to watch and gain from them. The spreading of an already determined cultural agenda is what can be understood as democratising culture.

Kelly does not dismiss democratising culture outright, but he questions why ‘there is a centrally controlled and co-ordinated set of cultural outputs at all,’ before going on to ask ‘who is it that selects the content of this set, and on whose authority [do] they do so.’ Kelly’s argument is that what is deemed to be high culture is never neutral, but rather serves the interests and reinforces the values of only a small group of society. It follows therefore, that democratising this culture might not be as liberating and enriching as intended, but could instead be seen, in Kelly’s words, as ‘an oppressive imposition, a radical monopoly exerted by a certain way of seeing and organising experience.’

It is important to make clear at this point that according to Owen Kelly taking an already determined cultural agenda to ‘the masses’ is contentious, not because ‘the masses’ should not have access to the great works of Shakespeare, or the art of Matisse for example. It is tricky because it positions the majority of people as passive consumers of forms of culture that have already been determined as good for them, rather than as potential creators of culture themselves.

This is where the concept of ‘cultural democracy’ comes in. Cultural democracy is premised on the understanding that culture is not something to be determined by a small group, but is instead created and circulated by everyone. It assumes that cultural production takes place within wider social contexts and feeds back into those contexts, helping to make sense of them. It is the creation of culture itself and the meaning that comes from this that is empowering and beneficial, not the consumption of pre-determined cultural forms. Hence, enacting cultural democracy involves giving people access to the means of making culture and cultural understanding as much as possible for themselves.

So how are these ideas relevant to gallery education and museum practice more widely? In my experience democratising culture and cultural democracy operate simultaneously within art museums on a macro through to a micro level. In very basic terms, initiatives including free entry, scholarly art historical lectures and talks that start with ‘in this painting we can see the artist was doing x’ represent the spectrum of democratising culture in action. At the same time, programmes that invite the public to take over spaces and create their own art within the museum, or events that bring in different cultural forms, such as house music or graffiti, or even workshops that begin with ‘what do you think the artist is trying to say here?’ align more closely with the idea of cultural democracy.

In my view, we need museums to be providing activities that both democratise culture and support cultural democracy. Crucially though, we need to be aware of the difference between the two and who might benefit more from each. That is one reason why these two concepts are so valuable.