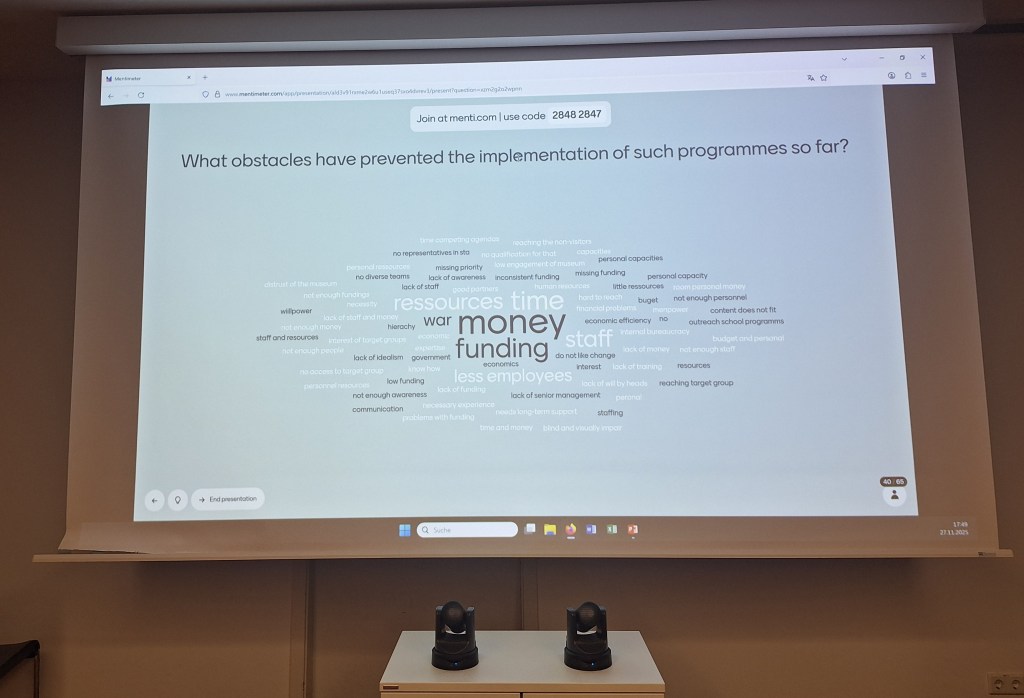

In the last nine months I have been fortunate to attend three seminars/conferences/gatherings of gallery and museum education professionals. In May 2025 I was part of the ‘Participation as Practice’ event at the Munch Museum in Oslo, where we focused on what it means to curate participation with artists for audiences with the art museum. In early November 2025 I attended the engage (the UK National Association for Gallery Education) Gathering in Bradford, where the focus was on reflecting back on visual arts engagement and gallery education from the past 50 years, to imagine practice going forwards. The last week of November found me in Berlin at the 4th International Conference of the Leibniz Centre of Excellence for Museum Education exploring the theme of ‘Diversity and Discourse: Engaging Museum Visitors in the 21st Century’ with colleagues drawn predominantly from science and natural history museums.

Each of these events were rich and rewarding, providing opportunities to hear from colleagues from the UK, Europe and further afield. Each offered insights into the variety of practice across museum and gallery education (historically, geographically, and in relation to different collections), and demonstrated the rigour of the research being conducted on and around these practices. Informal conversations during the events were, as ever, enlightening. I came away from each event with a clearer picture of the challenges the sector is facing, alongside the optimism and pragmatic choices colleagues are applying to make the sector fit for the complexities of the world today. The presentations and discussions reminded me why so much museum and gallery education work is highly theorised, but is also learnt through the doing of practice.

All three of these events demonstrated why it is vital for museum and gallery education professionals to gather together. Etienne Wenger and Jean Lave’s well-known theory of ‘Communities of Practice’ (CoP) is helpful here in rationalising why such regular group interaction is so valuable. A CoP can be described as a group of people who have a deep interest in something they do and, crucially, learn how to do it better through regular interaction with others. CoPs have three distinct characteristics; they share a common pool, or ‘domain’ of knowledge and understanding, which supports shared learning and participation; they are based in community, which allows for collaboration; finally their focus is on practice – on the doing – and how we can learn from this. These characteristics were very present at all three of the events I attended.

For example, despite having different focuses, themes came up in discussions at each event that reflected a shared domain of knowledge in terms of what constitutes best practice. The importance of time, for instance, and the need for trust in and from visitors. The value of experimentation and of authentic collaboration with audiences also surfaced, as did the unpicking of hierarchies of knowledge to allow for new and plural ways of knowing. Participants at each event brought their informed perspectives on these themes to the presentations and discussions. Dialogue within the community stimulated further debate and fresh insights for those present.

It was noticeable too, how many of the presentations at all three events were based around case studies of practice. Colleagues shared examples of projects they had been working on, in some cases to illuminate a theory in action, or to demonstrate how a problem or issue was being tackled through a specific intervention. We were shown not only the aims and outcomes of projects, but essentially we also got to see, hear and discuss processes and the evolution of practices, in some instances over many years.

It goes without saying that gallery and museum education is an incredibly diverse field. I met colleagues from small regional art galleries and huge national museums, from relatively well-funded research museums through to art galleries whose budgets have been brutally cut in recent years. Each colleague was dealing with their own histories, audiences, institutional priorities and wider policy directives. Yet the community of practice was clear to me, as was the enormous value to the members of this CoP of coming together to share and learn. It is, perhaps, because the field is so broad, that we need as many chances to share practice in person as possible.