In September I was fortunate to be invited to Columbus, Ohio by Dr Dana Kletchka, Associate Professor of Art Museum Education at Ohio State University. During my short visit I met with Dana, her wonderful students and colleagues from the Wexner Center for the Arts. I was also taken on a tour of the Columbus Museum of Art (CMOA) by Hannah Mason-Macklin, the Director of Interpretation and Engagement at the Museum. There is much I could talk about from this inspiring visit, but in this post I want to focus on the suite of spaces at CMOA designated as the JPMorgan Chase Center for Creativity, in the middle of which is ‘The Wonder Room‘.

On the CMOA website The Wonder Room is described as ‘as a place for intergenerational exploration, play, connection, and discovery. Art is displayed in unexpected ways, and custom, hands-on activities are featured prominently near great works of art to inspire creativity in this family-friendly space.’ In reality the space is brightly coloured, with objects to handle, climb on and creatively respond to. The invitation made explicit in the space is for visitors to experiment and connect with art and artists through play, and as the website says ‘to exercise their courageous imagination’.

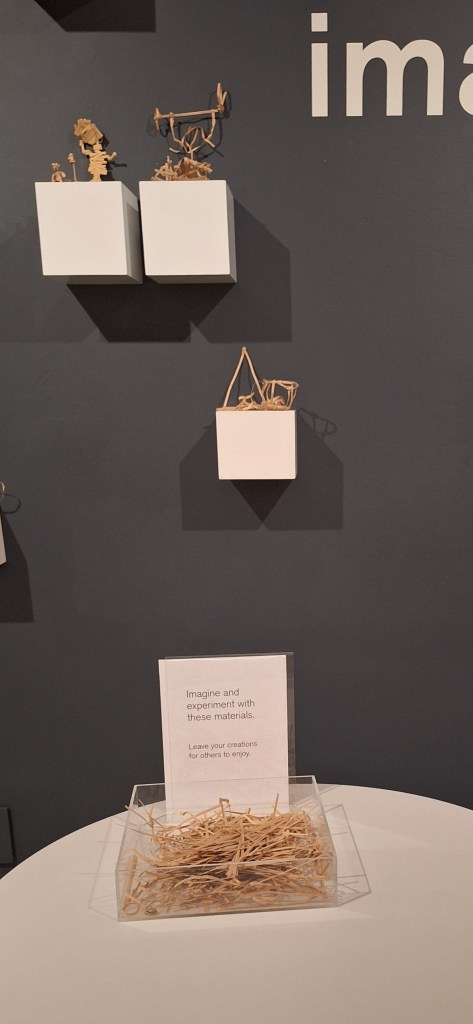

In the spaces circulating around The Wonder Room are further interventions that connect with the art in the museum through hands-on making activities. And although I was visiting the museum on a day when it was closed, I could easily imagine how engaging these spaces would be for visitors of all ages. The questions posed on the walls were open-ended and stimulating and the materials given for visitors to create with were simple, yet adaptable enough to allow for thoughtful creative responses.

Visiting CMOA reminded me how vital it is for art museums to provide opportunities for play and not only for children. Play, as writer and museum educator Claire Bown talks about in her ‘Thinking Museum‘ podcast is when we immerse ourselves in something for enjoyment’s sake. It is when we allow our imagination to range freely and when exploration and enquiry can bring joy and pleasure. Play empowers us and improves our social and emotional skills, whatever our age and playing with others brings us closer, allowing for human connection.

Increasingly art museums are providing spaces where play is actively encouraged. These spaces are generally curated by members of a Learning or Education department and frequently involve collaborations with artists. The brilliant ‘Come Think with Us’ initiative at the Munch Museum in Oslo is an example of Learning colleagues and artists working to create an immersive environment for intergenerational engagement and play. The most recent iteration of this being ‘Sofie’s Room‘, a collaboration with artists Roza Moshtaghi and Ronak Moshtaghi. Likewise the Uniqlo Tate Play interventions in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern are collaborations that actively invite the playful participation of visitors of all ages. In the summer of 2024, for example, the artist Oscar Murillo worked with Learning and exhibition curators to create ‘The Flooded Garden‘, an installation where visitors were invited to work together to create a huge canvas inspired by the work of Claude Monet.

Creating these playful spaces in the museum achieves many positive outcomes for visitors and institutions. Primarily they act as a draw for families, but in my experience adult visitors can also relish opportunities to make things and have fun in the museum. These spaces also allow for a different mode of collaboration with artists, which requires expertise and sensitivity on the part of curators. It takes considerable skill to create genuinely engaging interventions that encourage productive structured play. Too many directions and playfulness is no longer possible; too little structure and visitors may not know how to connect, or not have the confidence to experiment. I know from talking with colleagues working on these programmes how much work goes into creating these generous and generative spaces. It is a serious business designing for play.