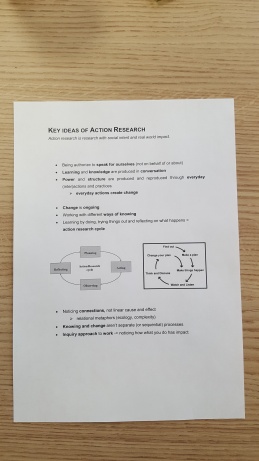

One of the ambitions for my research is to devise a framework for practitioner research in the art museum. To do this I have been looking into constructions of the ‘practitioner’ and the ‘professional’ and am trying to understand what characteristics are associated with these, particularly as they are often used interchangeably.

In many respects, the concept of the ‘practitioner’ is easy for me to grasp. If we understand practice as Jean McNiff and Jack Whitehead do – as ‘what we do’ – then practitioners are doers. They are those that operate in the complex and messy world of practice, developing ideas and knowledge from their experiences, as well as from theory, and using their expertise to resolve problems in action. As an art museum educator and researcher with a background in fine art, I see myself as a practitioner. In other words, as someone who has a certain amount of theoretical knowledge (some art history, some cultural, curatorial and pedagogic theory, some museology, some ideas around art making, for instance), coupled with the practical knowledge I have built up through working with materials, running programmes, collaborating with colleagues and the public, writing, speaking and so on. I draw on my theoretical and practical knowledge all the time and both are vital for me to do my work effectively.

But do I and others who work in museums qualify as professionals? My default conception of the professional (apart, obviously, from the questionable 1970’s television crime-action drama) is of a doctor or lawyer, or possibly a teacher. That is, someone with a clearly delineated occupation within a historically defined field. I was not sure if the relatively new and more nebulous occupations of curator or museum educator, for example, qualify. However, indicators suggest that they do. Nowadays organisations exist to represent the curator, with designated codes of conduct, which is one of the key features of a profession. Whilst a strong case for considering the educator as a professional has been put forward by Helen Charman in her 2005 text. Helen argues that the learning curator embodies the defining traits of the professional and enacts these in the museum context. It is worth looking at these characteristics in detail as they illuminate how and why the professional acts within society.

The first of the characteristics is specialist knowledge, acquired through education and training, which enables the professional to address specific situations and problems and act in the public good. This specialist knowledge gives the professional a degree of freedom and autonomy to make their own judgements and act accordingly. But with this autonomous status comes responsibility. Professionals can operate freely because of the trust that society invests in them to make good decisions and behave ethically and competently based on their expertise. It is these twinned characteristics – knowledge with autonomy, trust with responsibility – which inform how professionals work. Which suggests that these traits must underpin the actions of those professionals, amongst others, who curate and facilitate programmes in museums.

These four characteristics resonate with my experience of working as an educator and researcher in the art museum and align with the reading I’ve done and conversations I have had with curators on their practice. It is the case that museum professionals have considerable expertise and work is a relatively autonomous way and are trusted to act ethically and conscientiously. Educators in the UK, for instance, are not required to teach the national curriculum and curators are still largely in charge of designing their programmes. Both take their responsibilities to artists, to a collection and to the public very seriously.

But museum professionals work in a complicated and challenging environment nowadays and the fragility of the relationship between knowledge, trust, responsibility and autonomy was brought home to me when I read a recent blog post by Courtney Johnson, the Director of the Dowse Museum in New Zealand. In this post Courtney identifies four recent controversial situations in contemporary art galleries, where artists, activists and indigenous groups were moved to protest against decisions and actions the museums had taken.

I urge you to read the blog, so I won’t spell out the details here, but one observation that Courtney makes about trust and responsibility, has stuck with me. Having detailed the conflicting positions taken within the four case studies, Courtney questions the view often given that museums must retain their autonomy since they are ‘safe spaces for unsafe ideas’. She argues that this self-serving argument shields the institution, allowing it to act in its own interests and not those of anyone who might be damaged by the showing of an ‘unsafe’ work. It presumes a false insularity. Instead, as Courtney says – ‘museums are still capable of doing violence – unknowingly, or thoughtlessly, or because we value the presentation of art and art history over the individuals, communities and cultures who may have been harmed in its making, and may continue to be harmed in its public display.’

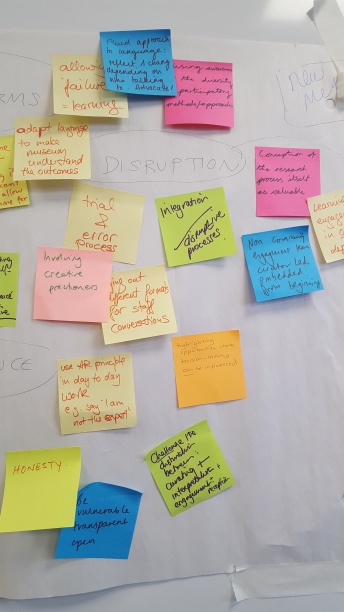

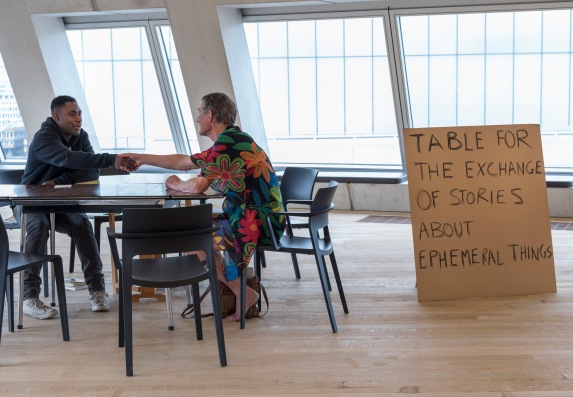

Courtney’s observation that galleries may act ‘unknowingly or thoughtlessly’ and that their actions can be unethical, suggests a profound failing in terms of professional behaviour. And perhaps more critically, it implies that museums cannot be trusted to act in the public good. Her words reveal one of the many dilemmas facing the twenty-first century art museum, that of how to open up a dialogue between the art on show and the world beyond the institution, rather than operating as a transmitter. To accomplish this, I believe, the museum and the professionals within it need to maintain their specialist knowledge, but acknowledge the expertise of others and work less autonomously if they are to maintain the trust of their audiences. This suggests that collaboration, the sharing of knowledge and an awareness of our own fallibility need to be added to the characteristics of the responsible museum professional.

I will be exploring these and other issues relevant to research in the art museum at two afternoon seminars at Tate Britain on April 26th and May 24th. Places are very limited, but if you are interested in attending please email me on emily.pringle.ep@gmail.com.